Stablecoins in Foreign Reserves: Opportunities and Challenges for Developing Central Banks

Introduction

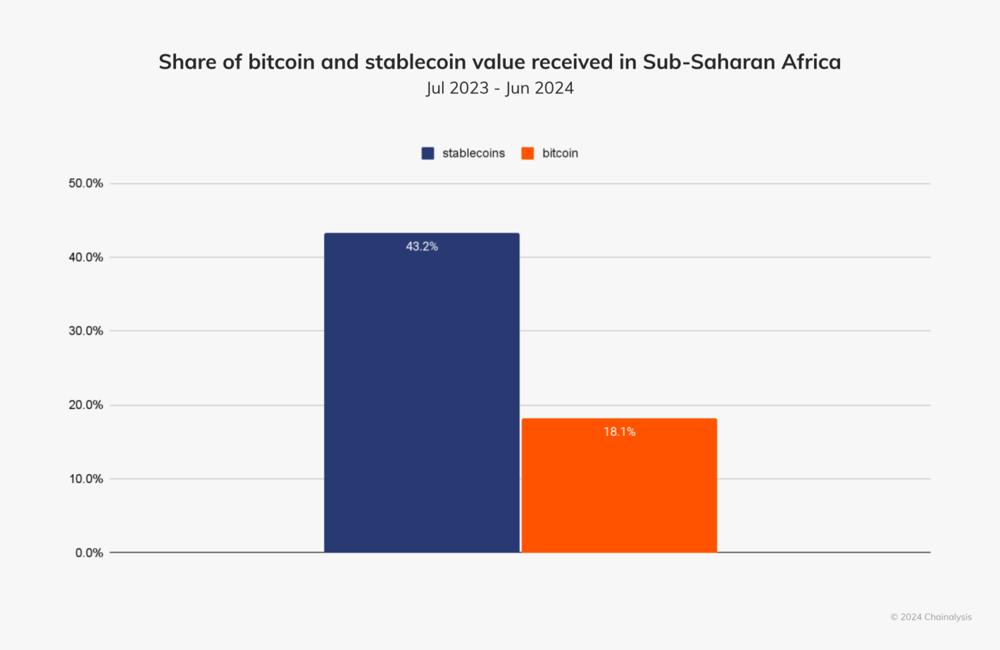

Central banks in emerging economies are increasingly exploring stablecoins – digital tokens pegged to fiat currencies – as potential additions to their foreign exchange (FX) reserves and liquidity toolkits. This interest comes as stablecoins gain traction globally, especially in developing markets where access to hard currency is limited. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa stablecoins now represent a significant share of crypto transaction value, far surpassing even Bitcoin[1].

Businesses and individuals in FX-constrained countries are turning to dollar-pegged tokens like USDT and USDC as substitutes for scarce dollars in trade, remittances, and savings[2][3]. Such trends raise an important question: Can central banks safely incorporate these “digital dollars” into official reserves or operational balances to bolster liquidity?

This report analyzes how key developing-country central banks might integrate compliant, transparent stablecoins into their FX reserves or use them in day-to-day liquidity operations. We first explain the concepts of foreign reserve management and operational working balances. Next, we examine the legal foundations, accounting standards (IFRS), and balance-of-payments frameworks relevant to including stablecoins in reserves. We then discuss the compliance risks and regulatory considerations central banks must address. Finally, we propose a pragmatic pathway for incorporating fully backed stablecoins (e.g. USDC, USDT) into reserve management. The aim is a clear, layered analysis in a neutral, professional tone – suitable for investors, policy analysts, and financial practitioners – on harnessing stablecoins’ benefits without compromising prudence or sovereignty.

Foreign Exchange Reserves and Operational Working Balances

Foreign exchange reserves are external assets held by central banks to ensure a country can meet its international payment obligations, stabilize its currency, and respond to economic shocks[4]. These official reserves typically include convertible foreign currencies (usually held as bank deposits or cash balances), foreign government bonds (e.g. U.S. Treasuries), gold, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), and reserve positions at the IMF[5]. Reserve assets must be high-quality, liquid, and readily available to the monetary authority in times of need[6][7]. For emerging economies, FX reserves provide confidence to markets that external debts can be paid and the local currency defended. Central banks thus invest reserves conservatively, prioritizing safety and liquidity over return[8][9].

Within a reserve portfolio, many central banks maintain an operational liquidity tranche (or working balance) alongside longer-term investment tranches[10][11]. The operational working balances are the portion of reserves kept in very liquid forms – such as cash, overnight bank deposits or other near-cash assets – to meet immediate foreign exchange needs. These needs include financing daily government FX payments, intervening in currency markets, or addressing short-term liquidity crunches. The liquidity tranche is invested in instruments that can be converted to cash at short notice with minimal value risk[9][10]. By contrast, the remaining reserves may be held in longer-maturity bonds or diversified assets to earn some yield (“investment tranche”), since they are less likely to be tapped in normal times[11]. In practice, developing-country central banks often struggle to maintain adequate reserves and liquidity buffers; many face chronic USD shortages and depend on reserves for currency stability[2].

Stablecoins enter this picture as a new form of foreign asset that could supplement traditional reserves or facilitate operations. A USD-pegged stablecoin (like USDC or USDT) is effectively a digital IOU for U.S. dollars: it maintains a one-to-one value by being fully backed by USD-denominated reserves (cash or safe assets) and redeemable on demand for actual dollars[12][13]. In theory, holding a reputable stablecoin is economically akin to holding a USD deposit or cash, minus the frictions of the banking system. Stablecoins settle instantly 24/7 on blockchain networks, which could help central banks transfer value or respond to market conditions outside of normal banking hours[14][15]. In developing markets where access to correspondent banks or physical dollars is limited, stablecoins offer a novel channel of dollar liquidity. Notably, private actors in such countries are already using stablecoins to bypass FX shortages – 70% of African countries face dollar shortages, and businesses increasingly obtain needed USD liquidity via stablecoins[2][3].

However, official reserve integration of stablecoins is not straightforward. By definition, official reserves should be under the central bank’s direct control and easily convertible to foreign cash[16][17]. Stablecoins are privately issued and rely on a third-party issuer’s promise and reserve holdings. As of 2024, leading financial institutions cautioned that crypto-assets (including stablecoins) do not yet meet the stringent safety, liquidity and low-risk requirements for reserve assets[18][7]. Stablecoins are still only emerging as a trusted medium; they are not yet widely used for official payments and carry regulatory uncertainty[19]. Central banks thus approach them cautiously. The next sections detail how legal, accounting, and statistical frameworks could support (or impede) treating stablecoins as part of reserves, and what risks require management.

Legal Foundations and Accounting Frameworks for Including Stablecoins

In considering stablecoins for reserves, central banks must examine legal mandates and accounting standards to ensure these assets can be held on the balance sheet. Most central bank laws enumerate permissible reserve assets (typically foreign currencies, foreign securities, gold, and IMF assets). Stablecoins do not fit neatly into traditional categories, but a strong case can be made that a fully fiat-backed, redeemable stablecoin qualifies as a foreign currency claim or deposit. For example, under IMF definitions, foreign reserves include external claims on non-residents that are readily available for balance-of-payments needs[16][20]. A USD stablecoin held by a central bank would represent a claim on the issuer’s USD reserves (often held in U.S. banks or Treasuries) – effectively an offshore USD deposit accessible via digital token. If the stablecoin issuer is legally obliged to redeem tokens for USD on demand, the central bank’s holding has a clear contractual value. Legal clarification may be needed to explicitly allow “digital currency” or “electronic tokens” as reserve assets, but many central bank statutes have flexibility for “other foreign assets” or deposits, which could encompass stablecoins with minor interpretation. Notably, new regulatory regimes are formalizing the status of stablecoins: in the EU, the MiCAR regulation defines “e-money tokens” as stablecoins fully backed 1:1 by fiat and legally redeemable at par[21]. Such tokens are essentially treated like electronic money. The U.S. has also moved to regulate stablecoin issuers (via the 2025 GENIUS Act) as insured institutions holding high-quality dollar reserves[22][23]. These developments lay a legal foundation by ensuring that leading stablecoins are backed by safe assets and enforceable redemption rights, making them more akin to traditional reserve instruments.

Accounting standards support the inclusion of stablecoins on central bank balance sheets, provided the tokens are structured appropriately. Under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) – which many countries follow or mirror – a key question is whether a stablecoin holding is considered cash/currency, a financial instrument, or an intangible. IFRS guidelines from 2019 treated cryptocurrencies (like Bitcoin) as intangible assets in most cases, due to their lack of claim on an issuer. Stablecoins, however, can confer a contractual right to cash (fiat redemption), which places them in a different category[24][25]. If a stablecoin holder has an enforceable claim on the issuer for \$1 per token, the token meets the definition of a financial asset under IFRS 9 (essentially a receivable or deposit in substance)[24][25]. The asset can then be measured at either amortized cost or fair value, depending on the business model for holding it. In the context of reserves (which are held for liquidity and not trading profit), amortized cost (essentially valuing it at stable par value) would be appropriate – similar to how a demand deposit in a foreign bank would be accounted for.

Crucially, IFRS also addresses whether stablecoins can be reported as “Cash and Cash Equivalents” on financial statements. IAS 7 (Cash Flow Statements) defines cash equivalents as short-term, highly liquid investments readily convertible to known amounts of cash with insignificant risk of value change[26]. Fully-collateralized stablecoins are strong candidates to meet these criteria. In fact, recent guidance suggests some fiat-backed stablecoins can be treated as cash equivalents under IFRS[27]. Their design (full fiat backing, par-value redeemability, high liquidity) aligns closely with IAS 7 requirements[28]. If a central bank holds a top-tier USD stablecoin that has guaranteed 1:1 redemption and negligible depeg risk, it could justify classifying it as part of its “cash or foreign currency deposits” in reserves. Accounting experts note that under narrow conditions stablecoins may qualify – for example, a “Tier 1” regulated stablecoin with on-demand redemption and intraday liquidity might be viewed as equivalent to a demand deposit in USD[29]. The European Central Bank’s own accounting rules (which influence many emerging market central banks) haven’t explicitly addressed stablecoins yet, but the logical treatment would be analogous to foreign currency cash or an external deposit, given the token is just a digital wrapper around fiat funds.

That said, auditors will require evidence that the stablecoin truly behaves like cash. They will look at the contractual terms, redemption mechanics, market liquidity, and any risks. IFRS practice so far shows some caution: many firms have avoided presenting stablecoins as cash equivalents due to residual concerns about liquidity or operational risks[29][30]. A central bank would need to document why the chosen stablecoin has insignificant risk of value change – for instance, demonstrating that the token is fully reserved in cash/short-term treasuries, that it has never materially deviated from peg, and that redemption is practical even during market stress. If these conditions hold, accounting standards pose no major barrier to holding stablecoins; indeed, they can be reflected in reserve portfolios similarly to other foreign currency assets. As one treasury expert noted, aligning MiCAR-regulated stablecoins with IFRS treatment “removes valuation headaches” and lets tokens “closely resemble holding the underlying fiat itself”[31][27].

On the balance of payments (BoP) and reserves reporting side, standards are evolving. The IMF’s Balance of Payments Manual (BPM6 and upcoming BPM7) thus far do not list stablecoins explicitly in official reserve asset categories, but they implicitly accommodate them under “currency and deposits”. In practice, if a central bank swaps part of its reserves into USDC, the IMF template would likely record it as an increase in foreign currency deposits (item I.A.(1) in the Reserves Data Template) and should be disclosed in the notes as a holding of a digital currency claim. Central banks would need to be transparent, perhaps reporting stablecoin reserves under “Other foreign currency assets” if not counted in official reserves until consensus grows. There is precedent for excluding novel assets until they become common; for example, working balances of government agencies held abroad are sometimes omitted from official reserves if small and hard to measure[32]. A prudent approach could be to initially hold stablecoins as operational assets (for liquidity purposes) off the official reserve tally, and only later incorporate them into reported reserves once international guidelines recognize them. Notably, the IMF and BIS are actively studying crypto-asset classification. Draft BPM7 guidance indicates crypto assets with corresponding liabilities (like fiat-backed stablecoins) do qualify as financial assets in macroeconomic stats[33]. We can expect that as major economies regulate stablecoins, these tokens will be treated in global statistics similarly to foreign currency bank balances.

In summary, the legal and accounting framework is gradually falling into place to allow stablecoins in reserve management. Properly structured stablecoins are legally akin to e-money, and IFRS-compliant accounting for them (as financial assets or even cash equivalents) is feasible[25]. The door is opening for central banks to consider these instruments – but doing so also raises a host of compliance and risk considerations, which we address next.

Compliance Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Despite their promise, stablecoins introduce non-trivial risks that central banks must manage before integrating them into reserves or operations. Key considerations include:

● Counterparty and Credit Risk: When holding a stablecoin, a central bank is effectively taking on the credit risk of the stablecoin issuer and its reserve custodians. Unlike holding actual USD in an account at the Federal Reserve or BIS, holding USDC means relying on Circle (the issuer) and its banking partners to honor redemptions; holding USDT means relying on Tether – a private company with more opaque disclosures – to maintain its peg. If the issuer’s reserves are mishandled or their banking access is cut, the stablecoin could fail to hold value. Central banks must therefore vet the issuer’s financial strength, regulatory oversight, and reserve quality. Preference should be given to “compliant stablecoins” that are subject to rigorous regulation and audits. For example, USDC’s reserves are held largely in U.S. Treasuries and cash, with monthly attestations, and its issuers will fall under U.S. federal oversight[34][35]. Such transparency mitigates risk. By contrast, if an issuer has a history of reserve doubts or operates from a lax jurisdiction, a central bank should be extremely cautious. Even with top-tier stablecoins, there remains a tail risk of depeg – evident in March 2023 when USDC briefly traded below \$1 after one reserve bank failed, though it later repegged. Central banks need to limit exposure to any single issuer and possibly spread holdings across a couple of reputable tokens to diversify counterparty risk.

● Liquidity and Market Risk: While stablecoins are designed to be stable in value, their market liquidity can dry up under stress or outside of major trading hours. A central bank intending to use stablecoins for emergency liquidity must ensure there is a deep market or redemption facility to convert tokens to cash at any time. The Bid/ask spread on large stablecoin transactions could widen in a crisis, effectively imposing a cost. Furthermore, certain stablecoins can be suspended or frozen by their issuers (for legal compliance), which could instantly render them illiquid for the holder. For example, USDC and USDT issuers have blacklisted addresses involved in crime before – if a central bank’s wallet were mistakenly flagged or if sanctions regimes intervened, access to funds could be lost. Thus, central banks should maintain accounts/wallets with trusted exchanges or custodians to facilitate rapid conversion of stablecoins to fiat, and establish direct redemption arrangements with the issuer when possible. They should also treat stablecoins as highly liquid but not risk-free, possibly applying a valuation haircut in internal risk models (similar to how even top-rated foreign bonds are given some risk weighting).

● Operational and Custodial Risk: Managing digital tokens requires technical infrastructure and safeguards unfamiliar to traditional reserve managers. Private keys must be stored securely (ideally in hardware security modules or multi-signature wallets) to prevent theft or loss of funds. There is a cybersecurity risk – hackers have targeted crypto holders, and a breach of a central bank’s wallet could be a serious event. Central banks will need to implement robust custody solutions, either building in-house capacity or using reputable third-party custodians that specialize in digital asset security. Procedures for authorizing transactions (e.g. multi-person approval for transfers) should be in place to prevent internal fraud. Additionally, stablecoin transactions on public blockchains carry settlement risks (e.g. if the blockchain network were to halt or if transaction fees spike during congestion). To mitigate this, a central bank might hold stablecoins on multiple blockchain networks (many stablecoins operate on Ethereum, Tron, etc.) to have redundancy, and keep some capacity in reserve to pay for network fees when moving tokens. Overall, integrating stablecoins demands new operational expertise and contingency planning for tech failures.

● Legal and Regulatory Compliance: Central banks must navigate domestic and international regulations when using stablecoins. On the domestic front, if crypto-assets are not legal tender, the central bank must be sure it has the legal authority to transact and hold them. In some countries, existing laws or regulations may actually prohibit the central bank (and other financial institutions) from dealing in cryptocurrencies – often due to concerns about instability or criminal use. These rules may require amendment or exemption for the central bank’s policy purposes. Regulators will also scrutinize accounting treatment and disclosure; the central bank should disclose its stablecoin holdings in financial statements and perhaps in foreign reserve reports for transparency. Internationally, AML/CFT standards apply. Stablecoins have been criticized by FATF and others as a channel for illicit finance if not properly monitored[36][37]. A central bank using stablecoins needs to ensure it adheres to strict KYC (Know-Your-Customer) and sanctions screening for any counterparty it interacts with. For example, if the central bank buys stablecoins from a crypto exchange or OTC broker, that entity must be vetted for compliance. Ideally, the central bank would obtain stablecoins directly from the issuer or a regulated financial institution to minimize touching potentially tainted coins. Chain analysis tools can be employed to screen the blockchain addresses the central bank’s wallet interacts with, to avoid transacting with blacklisted addresses.

● Monetary Sovereignty and Policy Impact: A more subtle risk is how stablecoin usage might affect the domestic monetary system. Central bankers in emerging markets worry that if stablecoins proliferate, local currency deposits could shift into digital dollars, weakening the effectiveness of monetary policy and exchange controls[38][39]. Indeed, stablecoins make capital flight easier: citizens in countries with capital controls have used dollar stablecoins to move wealth offshore by swapping local currency for USDT, then converting to actual USD abroad[40][41]. If a central bank itself holds or transacts in stablecoins, it tacitly legitimizes them as an acceptable form of money. This could accelerate dollarization of the economy if not carefully managed. Policymakers must weigh this outcome – stablecoins can facilitate remittances and FX access (a benefit)[42], but also provide a “pressure valve” for capital outflows (a risk)[43]. To manage this, central banks might pair stablecoin integration with updated regulations: for instance, caps or reporting requirements on large stablecoin outflows by local banks and firms, so that using stablecoins doesn’t equate to unchecked capital flight. Moreover, central banks should continue advancing their own central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) or faster payment systems to provide safer digital alternatives. The presence of a CBDC (perhaps a dollar-linked one in a currency board regime, or a well-designed local currency CBDC) could reduce public reliance on foreign stablecoins over time.

● Reputation and Precedent: Finally, a central bank must consider reputational risk. Being among the first to hold crypto-assets could invite public criticism or political backlash if things go awry. Any loss or incident with stablecoin reserves would undermine confidence. Moreover, it sets a precedent for other institutions in the country. Regulators will need to coordinate messaging so that private banks or investors don’t misinterpret the central bank’s actions as an all-clear to take excessive crypto risks. The integration should be framed as a limited, tactical measure under strict risk management, not an endorsement of all cryptocurrencies. Engaging with international financial institutions (IMF, BIS) to explain the approach will also be important, given conservative views in those circles[18][7].

In summary, stablecoin adoption comes with a spectrum of compliance challenges – from ensuring the token truly functions like a safe foreign asset, to guarding against new operational vulnerabilities, to preserving monetary control. The good news is that many of these risks can be mitigated with proper safeguards and policy adjustments. The next section outlines a pragmatic pathway for central banks to test and integrate stablecoins while heeding these considerations.

A Pragmatic Pathway to Integrating Stablecoins into Reserves

Central banks in developing countries should take a phased, well-governed approach to include stablecoins in their reserve and liquidity management. Below is a step-by-step pathway that balances innovation with caution:

1. Develop a Regulatory Game Plan: The central bank must first establish clear legal authority and guidelines for using stablecoins. This may involve seeking an amendment or legal interpretation of the central bank act to explicitly allow holding and transacting in digital fiat tokens as part of reserves or working balances. The bank should also issue or obtain regulatory guidance classifying stablecoins appropriately (e.g. as foreign currency assets or e-money) so that their use by the central bank (and possibly other financial institutions) is grounded in law. Early engagement with the finance ministry, legislature, and domestic regulators is key to preempt any legal ambiguities. By setting the rules of the road – such as which stablecoins are eligible (perhaps only those meeting high transparency standards), what limits apply, and how they will be accounted for – the central bank creates a compliant environment for integration.

2. Choose Trusted Stablecoin Partners: Not all stablecoins are equal. The bank should conduct due diligence and select one or two “reserve-grade” stablecoins to pilot. Criteria include: full fiat backing with audited reserves; strong regulatory oversight or licensing (e.g. an issuer regulated in the US/EU with adherence to MiCA or similar rules); proven market liquidity and track record of maintaining the peg; and no history of major compliance lapses. Currently, USD Coin (USDC) and Tether (USDT) are the largest USD stablecoins – USDC is often lauded for its transparency and regulated status, whereas USDT has wider usage but historically less transparency[44]. A central bank might favor USDC for its compliance pedigree, while possibly also using USDT in small amounts given its market ubiquity (ensuring convertibility even in markets where USDC liquidity is thinner). The bank could also consider newer regulated coins (e.g. a euro stablecoin if euro reserves are needed, or others that meet its criteria). Importantly, formalize relationships with the issuers: the central bank can open an account or onboarding with the stablecoin issuer or a major authorized distributor, allowing direct minting and redemption. This minimizes reliance on third-party crypto traders and ensures access to liquidity (much like having an account with another central bank or the BIS).

3. Implement Robust Custody and IT Systems: Before transacting, the central bank should set up secure digital wallets and custody arrangements. This could mean deploying an institutional-grade crypto custody solution (many are available from established fintech firms and even traditional custodian banks now offer digital asset custody). Multi-signature wallets should be used so that no single person can move funds unilaterally – e.g. require 3 of 5 authorized signatures for any transfer, aligning with central bank internal controls. The wallet addresses and keys must be kept offline (cold storage) when not in use, or in highly secure hardware modules, to prevent cyber threats. The IT team should run thorough tests of small transfers in and out, monitoring for any technical issues. Plans for backup and key recovery (in case a key holder is unavailable or a device fails) must be in place. Additionally, the bank should integrate stablecoin holdings into its treasury management systems, so they are visible in real time alongside other reserve assets. Developing the capacity to monitor blockchain transactions (perhaps via block explorers or APIs) will allow the bank to track its stablecoin positions and any incoming/outgoing flows.

4. Start with a Small-Scale Pilot: The integration should begin at a pilot scale, treating stablecoins as an extension of operational FX balances. For example, the central bank could convert a modest portion of its short-term USD holdings (say 1–2% of reserves or a few million USD equivalent) into the chosen stablecoin. This amount would be enough to test functionality but immaterial enough that any loss or issue would not threaten overall reserves. The pilot can focus on a specific use case – e.g. using stablecoins to facilitate remittances or cross-border payments for government obligations. One scenario: the central bank uses USDC to pay one of its overseas suppliers or to transfer funds to an embassy abroad, instead of using a correspondent bank wire. Another scenario: supplying local commercial banks with stablecoins (in exchange for local currency) to meet dollar demand of importers on weekends or when cash USD is scarce, thus intervening in the FX market via digital means. During the pilot, closely observe metrics like conversion spreads, transaction speeds, system reliability, and ease of redeeming back to fiat. This phase should remain low-profile to manage public expectations – it can be disclosed in financial statements after the fact, but there is no need for broad announcements until proven.

5. Risk Management and Controls: In parallel with the pilot, establish a comprehensive risk management framework for stablecoin operations. This includes setting exposure limits (e.g. stablecoins cannot exceed X% of total reserves without further approval; no more than Y% with a single issuer to ensure diversification). Implement monitoring triggers such as alerts if a stablecoin’s market price deviates more than a certain basis point from peg, or if issuer credit metrics deteriorate. The central bank’s risk committee should review stablecoin holdings regularly, just as they do for other assets, and incorporate them into stress testing (e.g. scenario: what if stablecoin redemption is temporarily suspended – how else can we meet FX needs?). Audit and compliance teams should be involved from the start to audit the processes – for instance, verifying that the stablecoin reserves held by the issuer match tokens outstanding (this could be done by reviewing the issuer’s public attestation reports[35] or even engaging with the issuer for additional comfort). Additionally, put in place contingency plans: if a problem arises (say, a smart contract bug or regulatory freeze), how will the central bank respond? Perhaps keep a portion of reserves as a quick backup to replace the stablecoin if needed.

6. Gradual Scaling and Integration into Official Reserves: If the pilot phase is successful over a period of months or a couple of years – meaning the stablecoins function as intended, with efficiency gains and no security incidents – the central bank can consider scaling up usage carefully. This could mean incorporating stablecoins into its official reserve portfolio allocation (shifting a larger share of working balances into stablecoins). The central bank might formally include them in published reserve figures at this stage, with appropriate footnotes. By now, hopefully international statistical guidance would be clearer; if not, transparent communication can bridge the gap (e.g. “included in currency assets are \$X in fiat-backed digital currency”). The use cases can also expand: beyond just holding tokens, the central bank could deploy them in innovative ways, such as participating in cross-border swap networks or liquidity arrangements with other central banks via stablecoins. For example, two central banks could agree to swap stablecoin liquidity in each other’s currencies during off-hours – a task previously done only by large banks. Moreover, the central bank can encourage domestic financial institutions to interface with it using stablecoins for certain transactions, thereby building a broader ecosystem of compliant stablecoin usage under its oversight. Throughout, scaling should be done in line with improvements in the regulatory environment (both local and global). If new standards or laws impose additional safeguards (for instance, requiring stablecoin issuers to have access to central bank lender-of-last-resort facilities, as some proposals suggest[22]), the central bank should adapt its strategy accordingly.

7. Ongoing Oversight and Adaptation: Even after integration, stablecoins should be treated as a dynamic element of reserves, warranting ongoing oversight and policy review. The central bank should remain actively engaged with international working groups on crypto-assets, share lessons learned with peers, and update its internal policies as the landscape evolves. It must also continuously evaluate the macro implications – e.g. is stablecoin usage affecting local money supply or exchange rate in unexpected ways? If signs of undue dollarization appear, the bank might tighten the reins or complement stablecoin use with measures to strengthen confidence in the local currency. Conversely, if stablecoins prove largely beneficial (lower transaction costs, enhanced remittances, etc.), the bank could consider expanding their role or even issuing its own tokenized form of reserves (some have floated the idea of central banks issuing tokenized deposits or “stablecoins” of their own, backed 1:1 by official reserves[45][23]). The strategy should be revisited regularly by the central bank’s board or monetary policy committee, ensuring it aligns with broader objectives of financial stability and development.

By following these steps, a developing-country central bank can progressively harness stablecoins as a supplemental reserve tool. Real-world reference points are beginning to emerge: for example, reports indicate Nigeria is drafting regulations to recognize stablecoins for payments and is exploring their use to improve remittance flows[46][47]. Several countries in Asia and Latin America are likewise studying stablecoins as part of FX management amid dollar shortages[2][48]. The approach recommended here is generalizable – it emphasizes prudent selection, small-scale testing, and risk controls, which any jurisdiction can tailor to its context.

Conclusion

Stablecoins offer developing countries a double-edged opportunity in foreign reserve management. On one side, fiat-backed stablecoins (like USDC and USDT) present a digital extension of the US dollar and other reserve currencies, potentially enhancing a central bank’s ability to mobilize liquidity rapidly and extend financial access. They can supplement foreign exchange reserves by providing 24/7 dollar liquidity, ease cross-border transactions, and even reduce costs (for example, stablecoin-based remittances to emerging markets are far cheaper than traditional channels[42]). In an era when many emerging economies struggle with intermittent FX shortages and the need for efficient payment solutions, these tokens act as a pressure valve – an avenue for critical inflows and outflows when traditional pipes are clogged[3][40]. The accounting and legal analysis suggests that, with full backing and proper regulation, stablecoins can be treated comparably to other foreign assets on central bank balance sheets[28][25].

On the other side, stablecoins bring significant challenges and risks that cannot be underestimated. They effectively outsource a piece of national reserves to a private entity, introducing counterparty risk that must be meticulously managed. They also raise concerns around regulatory arbitrage and capital flight, as they enable money to move in and out of economies outside the conventional banking realm[39][43]. For central banks charged with monetary stability, this is a delicate balance – embracing innovation while safeguarding sovereignty. The prudent path is neither outright dismissal (which might leave a country behind the curve) nor uncritical adoption (which could jeopardize stability). Rather, as detailed in this report, central banks should proceed gradually, guided by robust legal frameworks, international standards, and risk management practices.

In conclusion, compliant stablecoins can be woven into the fabric of FX reserves and liquidity operations, but only with careful tailoring. They should be seen as complements, not replacements, for traditional reserve assets – a way to enhance flexibility at the margins of reserve portfolios and improve transactional efficiency. Key developing countries that adopt this approach will likely do so in a limited, closely watched manner, setting important precedents for others. Over time, if these digital assets prove their reliability and if global regulatory consensus solidifies, we may see stablecoins become an accepted component of official reserves – particularly in the liquidity tranches that demand immediacy. Until then, central banks must remain vigilant. By following international best practices (IFRS guidance, IMF frameworks) and heeding the unique risks of crypto-assets[7][30], they can navigate this new territory successfully. The ultimate goal is to harness the benefits of stablecoins – speed, access, and programmability – while maintaining the bedrock principles of reserve management: safety, liquidity, and trust[6][8]. With a thoughtful strategy, stablecoins could indeed become a valuable instrument in the toolkits of forward-looking central banks in the developing world.

Sources: The analysis above draws on a range of current sources, including IMF and World Bank guidance on reserve management[6][10], IFRS accounting interpretations for stablecoins[28][25], and real-market insights into stablecoin usage in emerging economies[2][42]. These references, indicated throughout by the inline citations, provide further detail and evidence underpinning this report’s findings and recommendations.

Disclaimer: This article does not constitute investment advice. For reproduction or reprint requests, please contact hello@xbank-labs.com